Post Category - ParentingParenting

Post Category - ParentingParentingKamal Ahmad is the President and CEO of the Asian University for Women Support Foundation. A native of Bangladesh who went on to attend Harvard and University of Michigan Law School, Kamal founded the Asian University for Women in 2008 with the goal to empower women across the globe by giving women with leadership potential, regardless of nationality, religion or economic background, a superior education and the support to make a difference in their developing communities and the world. We were able to interview Mr. Ahmad and learn more about the AUW, its important global impact, and how we can help support it.

What was your motivation to establish the AUW?

The Asian University for Women opened its doors in 2008, but the idea began long before that. Jack Meyer – AUW Co-Founder – and I met when we were both working at the Rockefeller Foundation, and quickly found a common interest in the search for effective pathways to sustainable development. We recognized that you can try to fix any one challenge in the developing world, but the problems will keep coming back. International development is a complex field because these problems are interconnected. Often the solutions to the problems provide only temporary relief. But if you’re looking for something that will address a huge range of challenges from the ground-up, what you could call a silver bullet, it’s women’s education.

With this in mind, Jack and I, along with a host of similarly-minded friends, began laying the groundwork for AUW around 2000. We were prompted to action by the conclusions of the Task Force on Higher Education and Society, spearheaded by Henry Rosovsky, former Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University, who became an important part of planning the initiative. AUW was envisioned to be a center for excellence where talented women could come together to learn from a liberal arts curriculum, with peers from different countries and cultural backgrounds who would become their partners in forming an international network of emerging women leaders.

That is what AUW has become. Our first class entered in 2008, starting with one and a half years of Access Academy and four years of the undergraduate program. The Access Academy is a very special component of AUW – it allows us to bring in women who are talented and show leadership potential, no matter their background. During Access Academy, the young women bring their English up to academic fluency, and also study world history, mathematics, and computer skills. Now the undergraduate program is making greater use of summer classes to streamline into a three-year program, so most students will spend four years in total at AUW.

We’ve graduated three classes so far, more than 350 women who are in graduate school or working on a cause they care about – such as education at Teach for Nepal and BRAC; on health security at Chemists Without Borders and the Bhutan Cancer Society; on sustainable development at the World Bank and Save the Children; and on civil society at Democracy International and Work for Better Bangladesh. About 20% of our graduates have gone on to pursue advanced degrees at institutions such as Oxford University, Columbia University, Brandeis University, Ewha Womans University, and Lund University (Sweden).

What is your role in all of it now?

I’m now at the AUW Support Foundation, the principal source of funding mobilization and communications for the Asian University for Women.

Tell us a little bit about your background/childhood growing up in Bangladesh?

I grew up in Dhaka, a city that has changed a great deal in the years since I lived there. I remember that accessible education for all interested me from early on – for instance, there was a train station near my home where orphaned children would gather, and I took to sneaking out after dinner to teach them from my homework. When I was 14, I founded a series of schools for children of domestic workers, a population that had very few options and still suffers from prison-like working conditions. The combination of my childhood in Bangladesh and my later years of education has always been a source of ideas that are motivated by international development.

What are some of the challenges that female students in Asia face?

In addition to institutionalized sexism that exists across the globe, women in Asia and especially in developing countries are barred from obtaining an education from the start due to several factors, from political volatility to male entitlement which leads to a devastating number of cases of violence against women. It is a vicious cycle, because these external factors can stop a girl from going to school, yet the solution to breaking this cycle remains giving these girls access to secondary and tertiary education. Education for many in the region is a way out. It is a way to avoid early marriage, a way out of the system of violence and abuse, and a way into discovery of one’s own ambitions and potential.

Even if women do have a chance to reach an institution of higher education, they might not have an amount, rigor, or history of schooling that prepares them well enough for that institution. This is something we thought about when we designed our curriculum, namely the Access Academy curriculum, which provides a year-long, pre-college preparatory program that offers intensive instruction in English language, mathematics, leadership development, and computer skills.

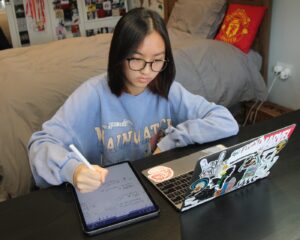

How does being a father to a daughter motivate you in this AUW mission?

My daughter was born right when AUW was in its nascent stages of development. Being a father motivates me in uncountable ways – but one that is particularly relevant to AUW is the chance to see someone discovering the world for the first time. I’m delighted that my daughter enjoys learning, and finds joy in number theory or coding, and that joy is a personal reminder of what we are accomplishing with the Asian University for Women. We are letting hundreds of talented women access the joy of learning, and channel it into their own dreams and leadership.

What are the criteria for admission to the AUW?

AUW receives more than a thousand applications every year for only around 100 spots in the next year’s class.

We work with country coordinators, usually NGOs who partner with us, in each country to promote the application season and administer the admissions test. In their application, the students have to describe their community involvements, write about an issue that is important to them, and of course we look for a commitment to academic excellence.

The most important part of the selection process is the interview – we look for signs of leadership potential, such as courage, empathy, and a sense of outrage at injustice. We find that the best predictor of success is how motivated the young woman is when she applies for university.

What makes someone standout in your pool of applicants?

When AUW recruits international students, we see a self-selection phenomenon. These girls have had to persuade their families and overcome many barriers – financial, personal, even just logistical – in order to arrive at the AUW campus. A young woman who can do that, and see the importance of a university education, is a very impressive young woman. So it is hard to say what makes someone stand out, since everyone at AUW stands out in their own way. We consider the key traits of leadership potential to be empathy, courage, and a sense of outrage at injustice. The particular experiences or ways in which an applicant embodies those traits are usually what draws our attention to them.

What are the factors that prevent women from getting an education in Southeast Asia?

This region is and will continue to be one of importance in growth and progress toward gender equality. In addition to institutionalized sexism and prejudice that exist all across the world, the issues of Southeast Asia include a devastating number of violent acts against women. In Bangladesh, more than half of women are married before the age of 18[1]. Child marriage prevents a girl from going to school, because as per tradition, she typically lives from that moment on in the household of her husband and his family, and her duties are frequently limited to housework and raising children. In a 2013 World Health Organization report, 41.7% of “ever partnered women” had experienced intimate partner violence. Violence—domestic and otherwise—intimidates and creates a culture that is not conducive to gender equality, let alone gender equality in the sphere of education. This in turn can lead to economic disenfranchisement, which has a positive correlation to a woman’s vulnerability to acts of violence. The call for action to economically empower young women by facilitating access to education, then, becomes clear.

While the situation seems bleak in this region, it is not without hope or potential. Ten of the countries represented in the AUW student body showed an annual GDP growth of over 5% in 2014. With this upward trend, it is crucial to include young women in the scope of progress, because only then can we have true progress.

How do you counter the entrenched cultural/social beliefs that prevent women from obtaining an education in these countries?

The greatest predictor of a student’s success is her motivation to learn. And it is often the case that a woman who grew up in Afghanistan, studying from her elder sister when the Taliban forbade girls to go to school[i], or a woman who was the first from her village in remote Pakistan to go to university, are extremely dedicated to their studies. These women are determined to pursue their higher education before they come to AUW, and once they are there, they quickly start to have an impact on their communities.

For example, a few years ago we accepted a student from a remote village in the Hunza Valley area of Pakistan. After her first year, her friends, neighbors, sisters and cousins had all heard about what she was experiencing at AUW. The next year, we received a huge wave of applications from that same village, and now we can see how one young woman prompted a cascade of changes in thinking. Once one person did it, other families realized that sending their daughters to a liberal arts school in another country, though not what you would call traditional, could be an extraordinary opportunity. Our students tell us that they are now seen as role models for their neighbors’ daughters.

Before the first class arrived at AUW, we were worried that ethnic or religious conflict would hinder the AUW mission. AUW brings together women from different religions – such as Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, and Christian students. We deliberately place first-year students with roommates from a different country. Even within the same country, there are often histories of ethnic conflict, such as in Myanmar or Sri Lanka.

But the girls have impressed us yet again. There is something about their eagerness to meet people who are different from them that helps them understand each other. The environment of collaboration where students all join together in clubs to teach English at local community schools, or learn guitar with each other on a Friday afternoon, is one that promotes friendships that span religious, ethnic, cultural, and political boundaries.

In 2012 we held a conference on women’s grassroots leadership. Afterwards, students were expected to return home and teach workshops in their home countries based on what they had learned. Our Tamil and Sinhalese students, whose families may have been in violent conflict with each other just years before, did conflict resolution workshops back home. At school, our Pakistani and Afghan students sit and cheer in the same café with Indian and Bangladeshi students to watch cricket matches.

Evidently, the environment at AUW and the types of women who choose to come to AUW are such that differences in religion or culture are reasons for connection, not conflict.

How many graduates go on to graduate or professional school?

About 20% of our alumnae have gone on to graduate school. We now have AUW alumnae at institutions around the world, including Oxford University, Columbia University, Lund University, and Ewha Woman’s University.

What role does Hong Kong play in the success of AUW?

Hong Kong has been a source of enormous support over the years. That’s why we recently launched a new Support Foundation in Hong Kong (August 2015) which will work to promote our global campaign to raise US$100m for a much-needed campus in Bangladesh and ensure the long term sustainability of the university. In addition, we’re continuing to work with local businesses and senior executives in Hong Kong to source internship opportunities and mentors for our students.

In Hong Kong, we have a dedicated pool of individual donors, as well as support from corporations who have chosen to make women’s education a philanthropic priority. For example, Li & Fung, through the Victor and William Fung Foundation, is sponsoring the full education of 15 students. We also envision even more cross-cultural collaboration between Hong Kong communities and AUW. For example, we are working on developing a faculty exchange program between AUW and some Hong Kong universities.

What is your favorite thing about Hong Kong?

On our most recent trip to Hong Kong, a couple of weeks ago, an AUW student speaking at our event was asked the same question and enthusiastically answered that she loved the perfect mix between nature and city that can be found here. I would have to agree: Hong Kong strikes the balance between sustainability and innovation, and is an amalgam, too, of many cultures. The rigor of the city is evident in its people, who are all motivated to create positive change in their communities and for women, and we’ve felt a tremendous amount of support here in our endeavors to facilitate higher education for women of all backgrounds in Asia and the Middle East.

What is your vision for the AUW? What would you like it to become in the next 10 years?

My vision for AUW is that it will grow to be the standard for education in the region. Liberal arts is a new concept in South Asia. You could say that focusing resources on women’s higher education is also a new concept – but I firmly believe that it is crucial for developing the full leadership potential latent in every country.

Ten years from now, AUW will be a much larger university than it is now. We have only been operating for about seven years, and our student body is around 500. We are operating out of rented facilities, but as I mentioned, we have the land on which to build a permanent campus – and a beautiful campus master plan by architect Moshe Safdie. We have just launched a campaign to raise $100 million in order to complete the first phase of campus construction and establish an endowment. In order to truly fulfill the vision of AUW, we will need to bring in more students. The permanent campus will be able to house and educate more than 1200 at once – a large jump from our current size. Our original plans also included several graduate degree programs, so that our alumnae could be fully equipped to start advanced professional work when they return to their communities.

How was the location of Chittagong, Bangladesh decided?

There are two main reasons, one philosophical and one more practical.

First, we believe it is crucial for this university, a center of excellence dedicated to women’s education and leadership, to be located in the region itself. Its very visibility declares the importance of women’s education. Most importantly, establishing the university in the region means that these women are not going to be plucked from their home countries, never to return. These women want to work on issues in their home countries, and we do not want to contribute to brain drain by pulling them out of the region for their education. We’re delighted that so many of our graduates have gone on to graduate schools all over the world, but these women are no doubt committed to using their skills for improving the communities they come from.

Next, once we understood the importance of establishing AUW in the region, we needed to find a country where AUW could operate freely. Bangladesh turned out to be the best place – in 2006, the Parliament of Bangladesh ratified a Charter which grants AUW institutional autonomy and complete academic freedom. These are rare components in a South Asian institution of higher learning – often it is a head of state who serves as Chancellor or has veto authority on hiring or curriculum decisions. AUW, by contrast, is free to develop the curriculum and recruit the faculty and staff it considers to be the best suited for its mission.

The particular location of Chittagong within Bangladesh is also related to the gift of land that we received from the Government of Bangladesh. AUW now has about 140 acres of land, located just outside of Chittagong, which we plan to use for building our permanent campus in the coming years.

How can one get involved in supporting the AUW?

AUW is a mission that benefits from all levels and types of support. In Hong Kong in particular, we’re looking for individuals and businesses that can support us by: sponsoring a student; hosting an intern; becoming a mentor to one of our students (this can be done via Skype or email); or contributing your skills and expertise to one of the Sub Committees of our new Hong Kong Foundation Board.

Internships are a particularly crucial part of the AUW education because we want our students to have real-world experience applying knowledge to practice before they graduate. A number of local Hong Kong organsiations have reported glowing experiences from hosting AUW interns for the summer – including The Women’s Foundation and Li & Fung.

More generally, an individual might sponsor a student’s flight to her home country for a summer project by donating $800; or an individual might visit campus and teach a workshop on his or her area of expertise. For example, last summer, visiting faculty from Harvard Medical School and Yale School of Medicine volunteered their time to teach a course on Global Mental Health.

What’s your greatest piece of advice you can give to parents who want to raise strong daughters?

At AUW, we want to instill in our students that they exist independently of others, and especially of men. A student told me recently, “There is a saying that when a girl is young, she is beneath her father. When she is married, she is beneath her husband. When she is older, she is beneath her son. We should change that.” Women’s empowerment means the power to be fully yourself, to have your successes, failures, and dreams be your own, instead of an echo or a byproduct of another’s.

So often we say that we should educate a woman because it will positively affect the health of her children, the economy, and the community’s stability. Yes, I do believe that women’s education is the solution to several of the pressing issues around the world today. However, a woman’s right to education also has inherent value for the woman herself. It has the power to enrich her life and allow her to define her happiness on her own terms.

Yet another student said, “AUW has taught me to become someone—not someone’s wife or daughter. Someone.” My advice to parents who want to raise strong daughters, then, is to allow them to be someone.

What’s the best piece of advice you could give to women in countries like Afghanistan and in South Asia who face opposition and barriers to access primary level and higher education who dream of attending a school such as AUW?

I would like to quote one of our graduates, a young woman named Marvah Shakib (who happened to be in Hong Kong at our events in August). She said, “I believe education is power for every human being, especially for women, that can change their present, future, their family’s status, and power relations for the better. I would advise them to empower themselves with education, build their capacities and be their own heroines. They have the capability, then they should never give up.” To me, this means that young women should remember that they have a great personal power. There is strength in numbers, and strength in collaboration, and AUW itself encourages its students to form international networks – but an individual, a single woman, is also an empowered being.

My other advice to young women who face oppression or barriers, which complements the first, would be to remember that they are not alone. There are about 30 million girls around the world who are prevented from attending school[ii]. At the same time, there are many more millions of women who have overcome the obstacles that they encountered, and who have used education to improve their lives and the lives of others. To the young woman who is struggling to attend school because she has to walk several miles each way, or who is arguing with her parents about whether she could continue to 10th grade or get married, I would tell her to remember Marvah’s words and be her own heroine.

[1] “Child Marriage Facts and Figures.” International Center for Research on Women, 2010. Web. 6 Aug. 2014.

[i] This anecdote is from a 2014 graduate from Afghanistan, whose elder sister secretly taught neighborhood children what they would have learned in school, and claimed she was only teaching the Quran when the Taliban questioned her.

[ii] http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ED/GMR/images/2011/girls-factsheet-en.pdf

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All